Online retailing has grown at a phenomenal rate, particularly during lockdown, but the advent of ‘dark stores’ has blurred the boundaries between internet and bricks-and-mortar shopping and presents new challenges and major concerns for local retailers.

by Professor Leigh Sparks

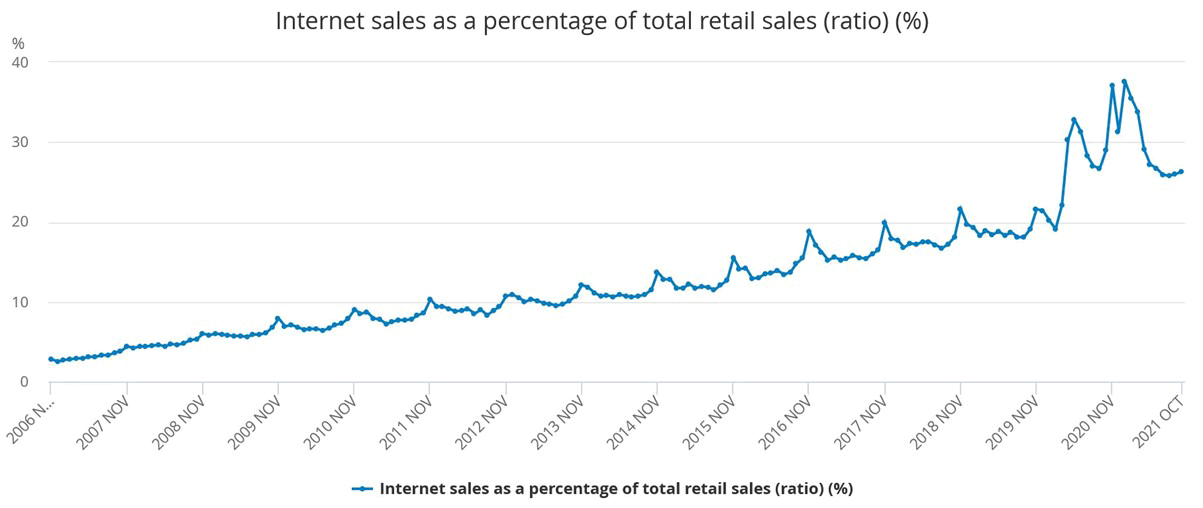

Online retailing is now close to 30 years old. It has seen an almost relentless growth over much of this period, accelerated by events such as Black Friday and Christmas, and more recently super-charged by the pandemic and lockdown. The graph of the increasing penetration of online sales in the UK has become well known.

What is meant by online or internet shopping seems to be changing though. The general understanding of online retailing is perhaps a retailer selling by a website or app and remotely fulfilling the order from a distant distribution centre.

Online giant Amazon is a classic incarnation of this, but it is a standard model across much of retailing.

A second variant of online retailing uses the same starting point of an app or a website, but with the fulfilment coming from a/the local store. Tesco started with this store-based model and achieved great first mover advantages and national coverage. In some situations, and again Tesco is an example, retailers began to organise urban fulfilment from ‘dark’ stores; stores not open to the public but designed to satisfy high online demand. This gives penetration and coverage in dense urban areas, but without compromising store operations.

In the pandemic we saw a major expansion of a local model of store fulfilment, with local fulfilment from local convenience stores. Indeed, it was one of the elements of the success the convenience store sector has had over the last 20 months of Covid. Services such as Snappy Shopper, Appy Shop and Jisp have emerged to help this process, and it is becoming increasingly common.

This local concept has developed further such that speed of delivery has become a general focus with within 15, 30 or 60 minutes promised. Some of this can be store-based but increasingly we see a trend to local ‘darkness’ as in dark kitchens or dark convenience stores. Such “stores” offer a cut down range in small operations and focus on fast local delivery. Others are basing operations on existing stores. This market is exploding and entrants such as Getir, Gorillas, Jiffy, Zapa and Weezy are the tip of a growing iceberg. Tesco offers its Whoosh service (see also Sainsbury Chop Chop) and will conduct a trial with Gorillas using a unit within spare space in a Tesco store. With Deliveroo Hop teamed up with Morrisons and Ocado and Zoom, ultra-fast delivery is in a rapid experimentation and development phase.

There are many issues in this online model, not least sustainability and environmental aspects, though these are mitigated in a local home delivery model, especially if returning to “old-fashioned” methods such as bikes. For the large multinationals there remain tax questions. The popularity of ultra-fast delivery asks questions of society and economy – it is hard for me to shake an analogy of a immobile Queen Bee (the consumer) being serviced by hordes of worker drones (the deliveries) – which is not what I think of as community.

There are concern over with “dark” operations and especially perhaps the smaller darker formats. Dark convenience stores may be on industrial or warehouse sites or possibly on car parks deemed redundant or under used. They take life and business away from neighbourhoods, communities and high streets. They are also likely to be business rated as non-retail businesses and so gain a cost advantage from this (and other operations) when compared to traditional convenience and retail sites. This is despite essentially performing the same basic function. Staffing via the gig economy will be different to physical stores. Our thinking about costs and competition, and comparisons with traditional operations, trail the business reality.

This changing face of online retailing and its fulfilment raises some fundamental issues about how retailing integrates into our communities and how its services should be valued. Convenience stores are so much more than fulfilment sites; but, if we don’t think through the implications of ‘dark’ convenience fulfilment sites then we risk damaging traditional retail business to the detriment of many. Some of their advantage stems from what they offer; some is due to the reduced cost base they can get away with. Either way they need to be treated seriously.

Professor Leigh Sparks is Professor of Retail Studies and Deputy Principal at the University of Stirling.